Case study

A team was building a stock-keeping system which was responsible to manage stocks of products in a facility. The system should be able to decrement the stocks as part of order demand and give an visibility into which stock is available in which facility. As part of this system design, they team designed a simple schema similar to the one below. The schema captured the product(SKU), facility(store/warehouse) and availability_count(total no of stock in that facility) to start with and decrement the ‘availability_count’ as and when the orders/reservations were placed.

This table had around 1000 rows initially.

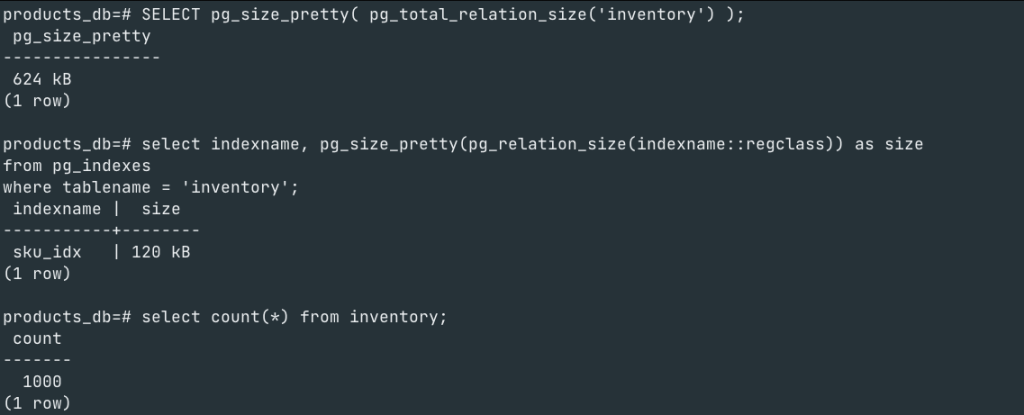

Let’s look at the table size and index size for this table

Days past by and the team started noticing couple of issues

- slow updates – decrement to the ‘avialability_count’ column was slow or taking time at peak concurrency.

- In-efficiency in storage

Updates takes row-level lock and when concurrency is in play, the locks are a pain and take additional time, but we cannot get away as they are there for a reason.

In-efficiency in storage – well, this is what we are going to zoom into for this post.

Let’s simulate a scenario where multiple orders were placed and decrements happened. We have used a function to simulate the decrements ~8000 transactions were executed as a part of this simulation. Below is the table & index size post the simulation

If you notice, we have not inserted any new rows, the same 1000 rows remain, however the table size on disk has increased 4x to what it was and the index size has increased 3X to what it was.

How?

Let’s learn 3 postgres internals

1. There are no updates – only deletes+inserts

Postgres uses MVCC technique for handling concurrency. As a part of MVCC, all updates create a new version of the data, while retaining the old version which is cleaned up later.

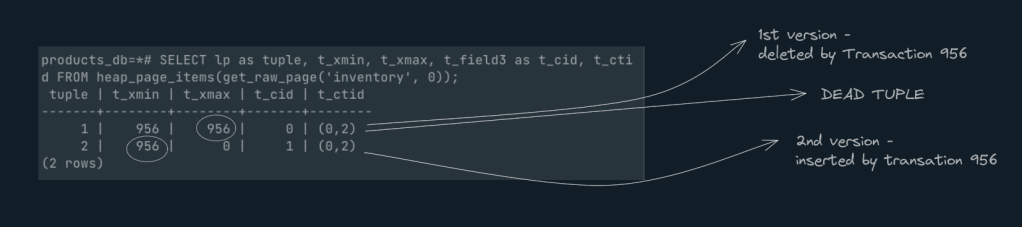

Let’s zoom into the tuple and its structure

xmin – tells which transaction has created that tuple

xmax – tells which transaction has deleted it.

Every transaction has a unique number which isolates it from other transactions. You can use the query below to know the transaction number of the current session.

select txid_current();So, let’s insert a new row into our inventory table and see the ‘xmin‘ value

As you see, the new row is part of a tuple whose ‘xmin‘(956) is pointing to the transaction-id(956) which created it.

Lets update the inventory table by decrementing its ‘availability_count’. Now postgres creates 2nd version of the tuple with updated values

In order to see the first version which was deleted, we use the page view extension here and query for that page.

As you can see above Tuple1 has ‘xmax‘ with a value 956, meaning this tuple is a dead tuple and won’t be considered for any queries.

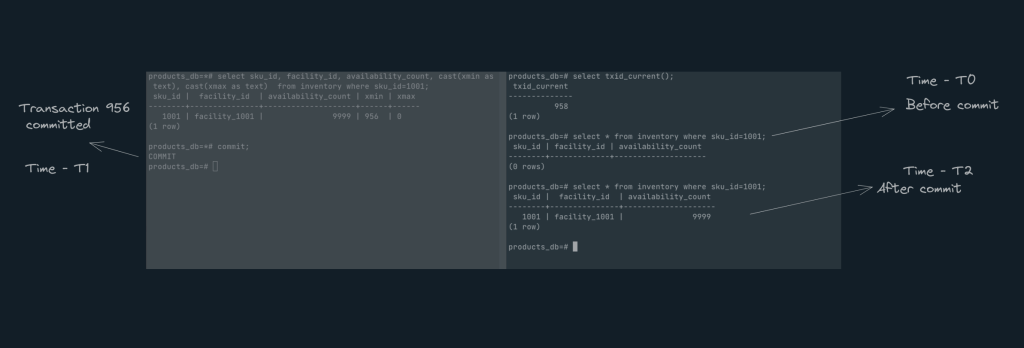

Let’s open 2nd session and understand the transaction id in both sessions and execute a bunch of queries as below

| Session1 | Session2 |

| Transaction no -956 | transaction no -958 |

| insert new row with sku-1001 | |

| Update row with sku-1001 | |

| select * from inventory where sku=1001 -> 0 rows | |

| commit | |

| select * from inventory where sku=1001 ->1 rows |

As you can see the isolation level used here is ‘Read committed‘ and hence ‘transaction-958‘ cannot see the row that ‘Transaction-956’ created until it is committed.

Because of this process, data versions happen leading to higher disksize and index size.

2.The dead tuple & bloat

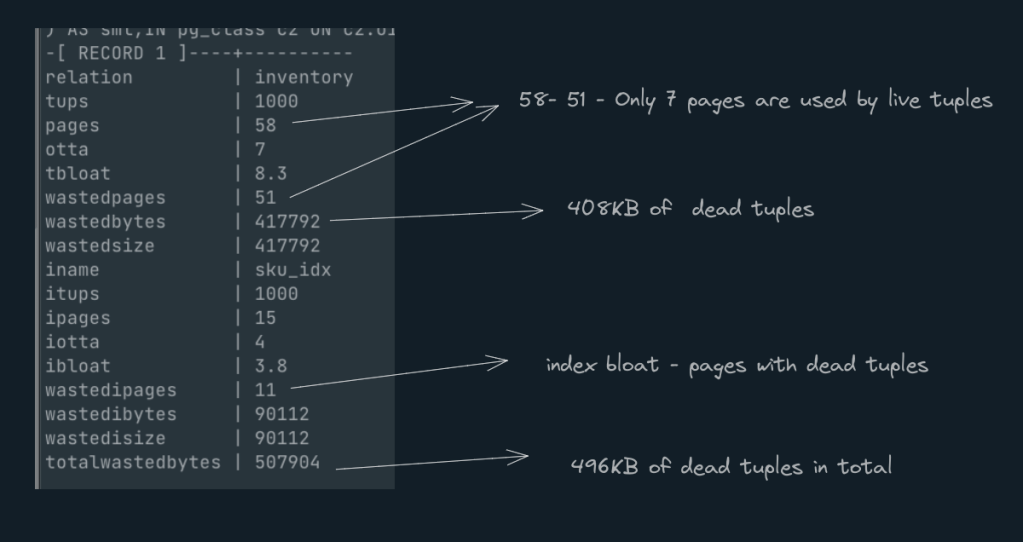

All tuples that has ‘xmax‘ value non-zero are dead tuples. In the above usecase, you will see that for 1000 live tuples, there is 3X dead tuples increasing the no of pages for tables and indexes.

Table/index bloat occurs on all pages that have a high percentage of dead tuples compared to live tuples.

Lets run a query to identify the table bloat for our inventory table. *Attached the query at the end

Well. How is postgres managing this?

Will Postgres make use of the dead tuple space by replacing it with newly inserted rows later on?

3. Vacuum

Saving grace: the Vacuum. Similar to grabage collection, vacuum frees up space for new rows by removing all of the dead tuples from index files and table files. In other words, the spaces are not regarded as free until the vacuum is run. So, it’s crucial to continually run the vacuum to ensure these dead tuples are cleaned.

Vacuuum can be triggered in auto mode or manual mode.

Auto Vacuum:

Postgres automatically triggers a vacuum on tables based on the configurations. Many runtime configurations can be tweaked for a particular use case. Here are a few critical ones to look for.

| Configuration | Description | sensible default |

| autovacuum | on/off | Ensure this is turned on |

| autovacuum_vacuum_threshold | Minimum number of tuple updates or deletes prior to vacuum. | Configure based on table requirements |

| autovacuum_vacuum_scale_factor | Number of tuple updates or deletes prior to vacuum as a fraction of reltuples. | The default is 0.2(20% of table size) |

| autovacuum_vacuum_cost_delay | Vacuum cost delay in milliseconds, for autovacuum. | This is a feature to slow down autovacuum, sometime running on big tables will cosume a lot of resource in particular CPU. |

Refer here for more details

Vacuum

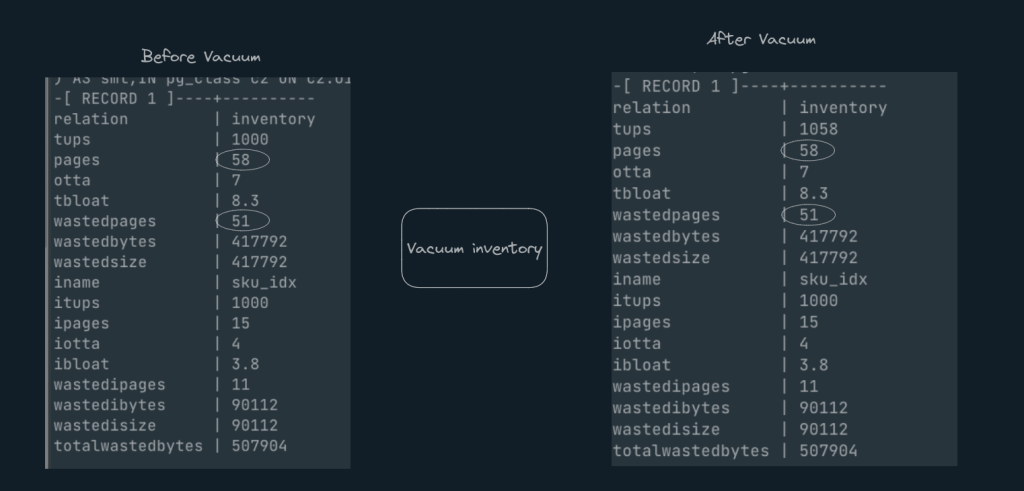

You can also run ‘Vacuum <<table name>>’ command to kickstart the vacuum process manually or as part of archive job. Let’s try to execute this on the inventory table and see the result

Well, nothing has changed even after Vacuum. why?

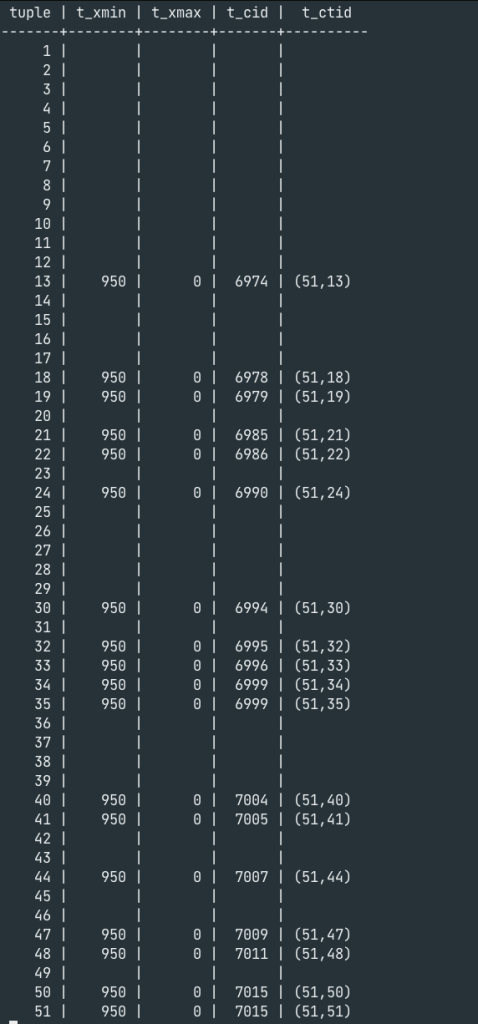

Lets inspect some page and see if the dead tuples are there are not

Inspecting page1

Inspecting page 51

The empty space in tuples 36 through 39, for example, shows that the dead tuples have actually been eliminated. Obviously, this can be used to fill in the newer rows. But can’t Postgres make fewer pages with only live tuples instead of 58 pages with empty space?

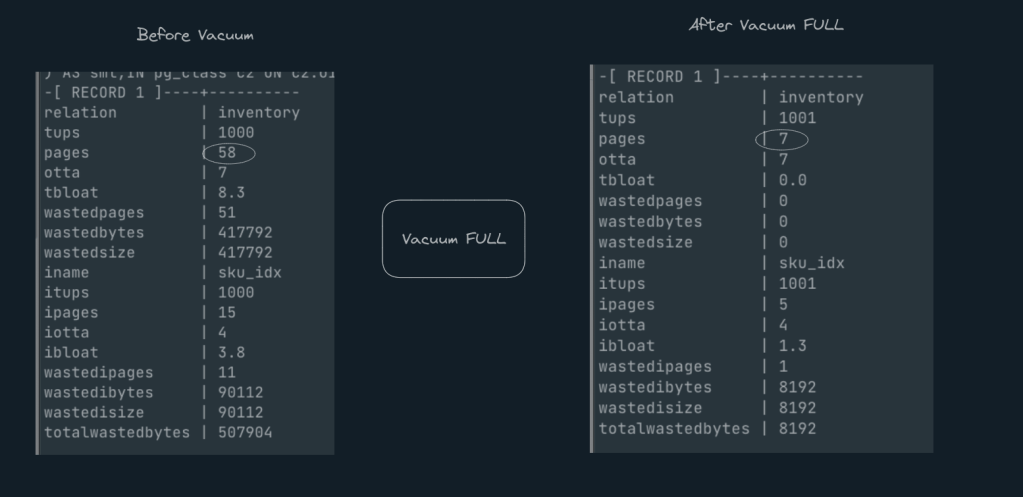

Vacuum Full

Vacuum Full does exactly the same as what we are looking for, which is efficiently reduce the pages by simply arranging all the live tuples

Lets see how this looks like

Wow. Just as expected. from 58 pages to 7 pages.

Note: – ‘Vacuum full‘ takes a table level lock which will impact any read/write queries happing on this table for other clients. hence, its recommended to run ‘Vacuum Full‘ only during off-peak hours or during maintenance window.

From a Developer’s lens

So what did we learn.

1. Storing counters in postgres is an anti-pattern.

We are not advising against updates, but rather that you would be better off using a redis instead of Postgres if your use case calls for a counter-like solution for the reasons mentioned above.

2.It’s crucial to understand the read/write patterns and set up Auto vacuum appropriately. An aggressive auto vacuum is an option for update heavy tables, while defaults are an option for insert heavy tables.

3. To run vacuum full and re-index indexes, it’s crucial to have archival/purge jobs running periodically and at off-peak times.

Useful Queries

1. Identify Table and index bloat

SELECT

tablename AS "relation", reltuples::bigint AS tups, relpages::bigint AS pages, otta,

ROUND(CASE WHEN otta=0 OR sml.relpages=0 OR sml.relpages=otta THEN 0.0 ELSE sml.relpages/otta::numeric END,1) AS tbloat,

CASE WHEN relpages < otta THEN 0 ELSE relpages::bigint - otta END AS wastedpages,

CASE WHEN relpages < otta THEN 0 ELSE bs*(sml.relpages-otta)::bigint END AS wastedbytes,

CASE WHEN relpages < otta THEN 0 ELSE (bs*(relpages-otta))::bigint END AS wastedsize,

iname, ituples::bigint AS itups, ipages::bigint AS ipages, iotta,

ROUND(CASE WHEN iotta=0 OR ipages=0 OR ipages=iotta THEN 0.0 ELSE ipages/iotta::numeric END,1) AS ibloat,

CASE WHEN ipages < iotta THEN 0 ELSE ipages::bigint - iotta END AS wastedipages,

CASE WHEN ipages < iotta THEN 0 ELSE bs*(ipages-iotta) END AS wastedibytes,

CASE WHEN ipages < iotta THEN 0 ELSE (bs*(ipages-iotta))::bigint END AS wastedisize,

CASE WHEN relpages < otta THEN

CASE WHEN ipages < iotta THEN 0 ELSE bs*(ipages-iotta::bigint) END

ELSE CASE WHEN ipages < iotta THEN bs*(relpages-otta::bigint)

ELSE bs*(relpages-otta::bigint + ipages-iotta::bigint) END

END AS totalwastedbytes

FROM (

SELECT

nn.nspname AS schemaname,

cc.relname AS tablename,

COALESCE(cc.reltuples,0) AS reltuples,

COALESCE(cc.relpages,0) AS relpages,

COALESCE(bs,0) AS bs,

COALESCE(CEIL((cc.reltuples*((datahdr+ma-

(CASE WHEN datahdr%ma=0 THEN ma ELSE datahdr%ma END))+nullhdr2+4))/(bs-20::float)),0) AS otta,

COALESCE(c2.relname,'?') AS iname, COALESCE(c2.reltuples,0) AS ituples, COALESCE(c2.relpages,0) AS ipages,

COALESCE(CEIL((c2.reltuples*(datahdr-12))/(bs-20::float)),0) AS iotta -- very rough approximation, assumes all cols

FROM

pg_class cc

JOIN pg_namespace nn ON cc.relnamespace = nn.oid AND nn.nspname = 'public' AND cc.relname='inventory'

LEFT JOIN

(

SELECT

ma,bs,foo.nspname,foo.relname,

(datawidth+(hdr+ma-(case when hdr%ma=0 THEN ma ELSE hdr%ma END)))::numeric AS datahdr,

(maxfracsum*(nullhdr+ma-(case when nullhdr%ma=0 THEN ma ELSE nullhdr%ma END))) AS nullhdr2

FROM (

SELECT

ns.nspname, tbl.relname, hdr, ma, bs,

SUM((1-coalesce(null_frac,0))*coalesce(avg_width, 2048)) AS datawidth,

MAX(coalesce(null_frac,0)) AS maxfracsum,

hdr+(

SELECT 1+count(*)/8

FROM pg_stats s2

WHERE null_frac<>0 AND s2.schemaname = ns.nspname AND s2.tablename = tbl.relname

) AS nullhdr

FROM pg_attribute att

JOIN pg_class tbl ON att.attrelid = tbl.oid

JOIN pg_namespace ns ON ns.oid = tbl.relnamespace

LEFT JOIN pg_stats s ON s.schemaname=ns.nspname

AND s.tablename = tbl.relname

AND s.inherited=false

AND s.attname=att.attname,

(

SELECT

(SELECT current_setting('block_size')::numeric) AS bs,

CASE WHEN SUBSTRING(SPLIT_PART(v, ' ', 2) FROM '#"[0-9]+.[0-9]+#"%' for '#')

IN ('8.0','8.1','8.2') THEN 27 ELSE 23 END AS hdr,

CASE WHEN v ~ 'mingw32' OR v ~ '64-bit' THEN 8 ELSE 4 END AS ma

FROM (SELECT version() AS v) AS foo

) AS constants

WHERE att.attnum > 0 AND tbl.relkind='r'

GROUP BY 1,2,3,4,5

) AS foo

) AS rs

ON cc.relname = rs.relname AND nn.nspname = rs.nspname AND nn.nspname = 'public'

LEFT JOIN pg_index i ON indrelid = cc.oid

LEFT JOIN pg_class c2 ON c2.oid = i.indexrelid

) AS sml;2. Query to inspect tuples in a page .

*you need to install a postgres extension – pageinspect

SELECT lp as tuple, t_xmin, t_xmax, t_field3 as t_cid, t_ctid

FROM heap_page_items(get_raw_page(<table>, <page_no));3. Query to view the number of pages for a given table

select * from pg_class where relname=<table-name>;

Leave a comment